Wildlife habitat connectivity - Projects & progress

Performance analysis

2023

WSDOT aims to improve the corridor with the most deer-vehicle collisions in the states

A 14-mile stretch of US Highway 97 between the towns of Riverside and Tonasket is the worst deer-vehicle collision area in the state, with approximately 100 deer-vehicle collisions recorded every year. With research suggesting around three times as many large animals are killed on highways than are reported in carcass removal data, it is estimated that approximately 300 mule deer are killed along this stretch of highway annually. This is partially because US 97 passes through the migratory path of Washington's largest mule deer herd and traffic volume, which averages around 4,600 vehicles per day, is low enough to encourage crossings but high enough to frequently result in collisions.

In addition to large mule deer herds, this stretch of highway is adjacent to habitat that supports many low-density, rare, or at-risk species, such as all three of Washington's native cats (Canada lynx, cougar and bobcat), as well as endangered grouse. Furthermore, species long absent from the landscape, such as pronghorn and threatened Canada lynx, are being reintroduced and will live near this highway, bringing new species into consideration.

Few safe crossing opportunities currently exist for wildlife along this section of US 97, and between 2019-2023, 413 large animals were reported as being hit and killed in this corridor, most of them mule deer. With the average cost of a deer-vehicle collision estimated at $14,014, the 413 large animal collisions recorded represent an economic impact of approximately $5.8 million. There was a 12% decrease in wildlife-vehicle collisions on this portion of US 97 recorded for the five-year periods between 2018-2022 and 2019-2023, which can likely be attributed to ongoing work intended to reduce collisions, currently focused on the northern extent of this area.

In 2019, WSDOT collaborated with Conservation Northwest to install one mile of wildlife barrier fencing attached to a pre-existing crossing structure over the Okanogan River at Janis Bridge. This wildlife barrier fencing helps prevent animals from crossing at unsafe locations and guides them to the safe crossing at Janis Bridge.

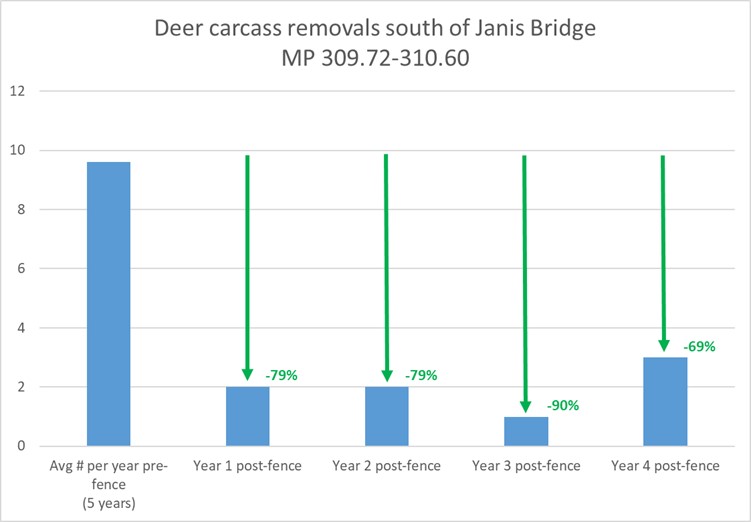

WSDOT has recorded an average of 2,500 safe mule deer crossings per year under Janis Bridge since the fencing was installed. Nineteen other species, from pheasants to cougars, have been recorded using the crossing since fencing was added. In addition, average annual deer-vehicle collisions in the vicinity of Janis Bridge have decreased by up to 90% annually compared to the pre-fence five-year average.

WSDOT, WDFW, and Conservation Northwest are working to secure funding for Phase 2 of this project, which will include two new wildlife crossing structures, fencing linking them together, and additional features to support connectivity and reduce collisions. Funding for Phase 2 will be requested from the federal government under the Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program using $3.7 million allocated by the state legislature for cost-sharing requirements. There is broad local, state, and Tribal support for building wildlife crossings in this area due to the potential increases to motorist safety and benefits to wildlife populations, as evidenced by the high crossing rates and reduction in collisions recorded over the past four years.

Collaboration leads to updating Washington's oldest wildlife crossing structure

WSDOT and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife built the state's first wildlife crossing structures in 1976 on Interstate 90 near North Bend. Since then, WSDOT has constructed more than 40 wildlife crossings and is frequently recognized as a leader in the field of road ecology.

One of Washington's first wildlife crossing structures recently benefited from new science and the hard work of Conservation Northwest staff and volunteers from the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, WDFW Master Hunters Program, and Snoqualmie Indian Tribe as they removed invasive Himalayan blackberry and the original fencing installed nearly 50 years ago, replacing it with a better design. The Upper Snoqualmie Valley Elk Management Group and Evergreen Mountain Bike Alliance also provided input on this project. In 1976, little was known about species-specific crossing structure needs. The original fencing alignment cut through the structure and over the years, Himalayan blackberry grew thick, constraining animal movements to a narrow pathway and reducing the feeling of openness that elk require to confidently use a wildlife crossing.

Overgrown blackberry plants and old fencing were removed and replaced with native plants and a new fencing design to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions and accommodate safe passage of elk. Several fence posts were left in place to provide bird nesting opportunities and plantings of service berry, ocean spray and elderberry are planned for this year.

State agencies collaborate to develop the Washington Connectivity Action Plan

The Washington Habitat Connectivity Action Plan is a collaborative partnership to prioritize places and projects that protect and enhance habitat connectivity statewide. The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife is developing the WAHCAP in collaboration with WSDOT and Conservation Northwest, with the primary goals of prioritizing both road crossing and landscape connectivity projects. The WAHCAP, which will be published in June 2025, will reflect existing conservation priorities and support ongoing or proposed connectivity work from tribes, partners, and stakeholders. WSDOT's previous prioritization frameworks, such as the Habitat Connectivity Priority Zones, will be used as the basis of the road crossing priorities.

Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians awarded $8.5 million to construct wildlife overcrossing

The Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians was awarded $8.5 million dollars through the federal Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program to design and construct a wildlife overcrossing on State Route 20 in the Hamilton-Lyman area. SR20 between Sedro-Woolley and Concrete ranks in the top 10% of worst elk-vehicle collision locations statewide, and as it is situated in the foothills of the North Cascades, there is a broad diversity of species inhabiting the area. As a result, WSDOT identified this location as a top 15 Habitat Connectivity Priority Zone. Using carcass removal, collision, and GPS-collar data, research identified four distinct collision and crossing hotspots associated with the movements of four elk sub herds. This allowed analysts to pinpoint locations to apply solutions, such as constructing wildlife crossings and fencing, which have been shown to consistently decrease collisions with animals by up to 90% while improving connectivity.

Puyallup Tribe of Indians awarded $216,250 to conduct wildlife crossing structure feasibility study

The Puyallup Tribe of Indians was awarded $216,250 through the federal Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program to conduct a wildlife crossing structure feasibility study on US Highway 12 in the Packwood vicinity. US 12 between Randle and north of Packwood ranks in the top 10% of worst elk-vehicle collision locations statewide. Situated in the South Cascades, rare and elusive wildlife like Cascade red fox, wolverine, and fisher are also present. As a result, WSDOT identified this location as a top 15 Habitat Connectivity Priority Zone. The feasibility study will identify the best locations for wildlife crossings based on biological and engineering opportunities and limitations. When complete, it will include conceptual designs and cost estimates for structures. This information is necessary to identify and apply for federal grant programs that fund wildlife crossing structure construction.

2022

Projects including terrestrial habitat connectivity and fish passage protect wildlife resources

The concepts of fish passage and terrestrial wildlife habitat connectivity are linked. Riparian corridors (where aquatic and terrestrial environments meet) comprise small portions of the landscape but provide disproportionately important ecosystem functions. These areas are commonly used by wildlife to travel between patches of suitable habitat, and in highly fragmented urban landscapes, represent some of the last remaining travel routes available.Completing terrestrial wildlife habitat connectivity and fish barrier removal work leads to engineering efficiencies and cost-savings. Combining these types of projects typically results in only minor cost increases over the fish passage-only plans, while constructing standalone wildlife crossing structures would be significantly more expensive. However, not all fish barrier removal projects offer the same potential benefits to terrestrial wildlife. Therefore, locations deemed important for terrestrial wildlife connectivity are prioritized using WSDOT's Habitat Connectivity Investment Priorities. If a project falls in or adjacent to a one-mile segment ranked high for either Ecological Stewardship or Wildlife-related Safety, it receives recommendations on how to enhance it for terrestrial wildlife passage.

The recently completed Indian Creek fish barrier removal project on US Highway 101 resulted in a wildlife underpass large enough to safely pass all species of animals on the Olympic Peninsula, including elk. Within weeks, a mink was recorded using the underpass and the first month of camera monitoring revealed several black-tailed deer herds crossing as well. Two years of pre-construction monitoring documented no native species crossing beneath US 101 using the old structure.

WSDOT developing statewide Habitat Connectivity Priority Zones

WSDOT is developing statewide Habitat Connectivity Priority Zones to help direct limited resources, including grant funding, to highway segments most needing wildlife crossing structures to increase habitat connectivity or reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions. The zones will be used to communicate priorities and coordinate solutions with partners.

Like the Habitat Connectivity Investment Priorities, the Habitat Connectivity Priority Zones are built around WSDOT's two-pronged approach to wildlife connectivity planning, utilizing Ecological Stewardship and Wildlife-related Safety categories. However, the HCPZ are characterized by longer, contiguous road segments ranging from approximately four to 30 miles in length. The HCPZ are distinct from the HCIP that rank the highway system at one-mile intervals which are primarily used for internal planning at WSDOT.

The top 15 Habitat Connectivity Priority Zones are expected to be published mid-July 2023, after an in-depth review conducted by government biologists, tribes, and environmental non-profit organizations.

Even though the HCPZ are currently in draft status, there are two locations that are indisputably Habitat Connectivity Priority Zones: US Highway 97 between Riverside and Tonasket, and Interstate 5 in the Castle Rock vicinity.

US Highway 97, roughly between the towns of Riverside and Tonasket, is the worst deer-vehicle collision area in the state. This approximately 14-mile stretch of highway is the scene of over 100 recorded deer-vehicle collisions yearly, resulting in significant property damage, wildlife mortality, and about two human injuries annually.

Research suggests around three times as many large animals are killed on highways than reported in carcass removal data, so it's estimated that at least 300 mule deer are killed along this short stretch of highway every year. This extremely high level of collisions is partially because this road passes through the migratory path of Washington's largest mule deer herd and the traffic volume (around 4,600 vehicles per day) is low enough to encourage crossings but high enough to frequently result in collisions.

In addition to large mule deer herds, this stretch of highway is adjacent to habitat that supports many low-density, rare, or at-risk species, such as all three of Washington's native cats (Canada lynx, cougar and bobcat), as well as endangered grouse. Furthermore, species long absent from the landscape, such as pronghorn and threatened Canada lynx, are being reintroduced and will live in close proximity to this highway, bringing new species into consideration.

Few safe crossing opportunities exist for wildlife here, and 468 large animals were hit and killed in this corridor between 2018-2022, most of them mule deer. With the average cost of a deer-vehicle collision estimated around $9,867, the 468 large animal collisions recorded in this 14-mile corridor represent over $4.62 million of economic impact.

In 2019, Conservation Northwest and WSDOT installed one mile of wildlife barrier fencing attached to a pre-existing crossing structure over the Okanogan River, Janis Bridge (at the northern end of the US 97 Riverside to Tonasket HCPZ). This wildlife barrier fencing helps prevent animals from crossing at unsafe locations and guides them to the crossing at Janis Bridge. In the three years since fencing was installed, WSDOT recorded an average of 2,500 safe mule deer crossings per year under Janis Bridge, representing 2,500 times a year that large mammals did not try to cross through traffic. Nineteen other species were recorded using the Janis Bridge crossing since the fence was completed. Furthermore, average annual deer-vehicle collisions near Janis Bridge decreased by 80-90% in the three years since the one mile of wildlife barrier fence was completed.

While successes have been recorded for the Janis Bridge project, Phase 1 only addressed one mile of the 14-mile Priority Zone. There is local, state, and tribal support for building wildlife crossings in this area due to the potential significant increases to motorist safety and benefits to wildlife populations. WSDOT and Conservation Northwest are working to secure funding for Phase 2 of this project, which will include two new wildlife crossing structures, fencing linking them together, and additional features to support connectivity and reduce collisions. Funding for Phase 2 will be supported by $2.7 million allocated by the Washington State Legislature.

Interstate 5 in the Castle Rock vicinity bisects a critical wildlife corridor linking the Cascade Mountains to the Willapa Hills, and by extension, the Olympic Peninsula. This approximately nine-mile stretch of interstate is one of only two locations identified along I-5 that could provide connections between these diverse ecosystems, and opportunities to bridge this barrier are dwindling due to rapid development of adjacent areas.

The I-5 Cowlitz to Toutle Rivers Priority Zone sees an average of 40,000 vehicles per day across six lanes of traffic, while 10,000 vehicles per day or greater is generally considered a total barrier to wildlife movements. Recent research indicates cougars west of the Interstate are genetically isolated from populations east of it, and I-5 and associated traffic were identified as the barriers limiting animal movement between habitats on either side. This area has not only been identified as a cougar corridor, but also a corridor for elk, black-tailed deer, and other species. However, safe crossing opportunities are currently limited in this zone.

2021

Butler Creek project combines terrestrial and aquatic connectivity efforts

The Butler Creek Undercrossing project on US 97 was completed in 2012 and improved habitat connectivity for aquatic and terrestrial wildlife alike. The project replaced a 10-foot diameter culvert, which was a fish passage barrier, with a 65-foot span bridge that allows passage for all animals. This section of two-lane highway historically experienced high deer-vehicle collision rates, which provided an opportunity to improve aquatic and terrestrial habitat connectivity while also reducing the potential for dangerous wildlifevehicle collisions.

To create a successful safe crossing for terrestrial wildlife, features were included such as wildlife barrier fencing and multiple wildlife jump-outs (safe exits for animals that find their way inside the fencing).

Since this project was completed, the annual number of wildlifevehicle collisions has decreased by 81% within a half mile of the fence ends in both directions. In addition, fish are able to access habitat upstream of the highway. There are roughly 500 recorded deer crossings per year at this location, and many other species also use the underpass, including black bear, bobcat, coyote, cougar, California ground squirrel, endangered western gray squirrel, wild turkey, raccoon, and great blue heron.

Janis Bridge project reduces deer-vehicle collision rate by 91% in the area

On US 97 near the Canadian border, the 12-mile stretch between Riverside and Tonasket is one of the worst deer-vehicle collision areas in the state. In addition to large mule deer herds, this stretch of highway is adjacent to habitat that supports many low-density, rare, or at-risk species—such as all three of Washington's native cats (Canada lynx, cougar and bobcat)—as well as endangered grouse. Furthermore, species long absent from the landscape, such as pronghorn, are being reintroduced and will live in close proximity to this highway.

Few safe crossing opportunities currently exist for wildlife here, and 452 large animals were hit and killed on this corridor between 2017-2021, most of them mule deer. With the average cost of a deer-vehicle collision estimated around $9,175, the 452 large animal collisions recorded in this 12-mile corridor represent over $4.15 million of economic impact.

In 2019, Conservation Northwest and WSDOT installed one mile of wildlife barrier fencing attached to a pre-existing crossing structure over the Okanogan River, Janis Bridge (at the northern end of the US 97 problem area). This wildlife barrier fencing helps prevent animals from crossing at unsafe locations and guides them to the crossing at Janis Bridge.

In 2020, the first year after the wildlife barrier fence was installed, WSDOT recorded 2,194 mule deer crossings at the Janis Bridge structure. That number increased to 2,432 in 2021 (cameras were down for 40 days, so actual numbers were higher). In addition, 18 other species were recorded using the Janis Bridge crossing in the two years since the fence was completed.

Average annual deer-vehicle collisions in the vicinity of Janis Bridge decreased by 91% (11 per year in 2017 down to one deervehicle collision in 2021) since the completion of the one mile of wildlife barrier fence.

Providing safe passage for wildlife in this 12-mile corridor (between Riverside and Tonasket) is a top habitat connectivity priority in Washington. Realizing this, the legislature recently awarded $2.7 million to begin addressing these needs.