Wildlife habitat connectivity

Highlights

2023

- WSDOT and its partners have recorded over 25,000 safe wildlife crossings since the first stage of Snoqualmie Pass East Project was completed in 2014

- WSDOT's US 97 Janis Bridge wildlife crossing project reduces annual deer-vehicle collisions by up to 90% near Tonasket in Okanogan County

- WSDOT removed 39,258 wildlife carcasses from state highways from 2019 to 2023

WSDOT aims to increase habitat connectivity and decrease wildlife-vehicle collisions

Habitat connectivity is how the landscape facilitates or impedes animal movement and other ecological functions. Roadways alter landscapes and can create barriers to these movements which are crucial to survival for many species. Furthermore, wildlife-vehicle collisions represent an ongoing danger to the traveling public and typically result in an animal's death. WSDOT is working to both increase habitat connectivity and reduce wildlife—vehicle collisions.

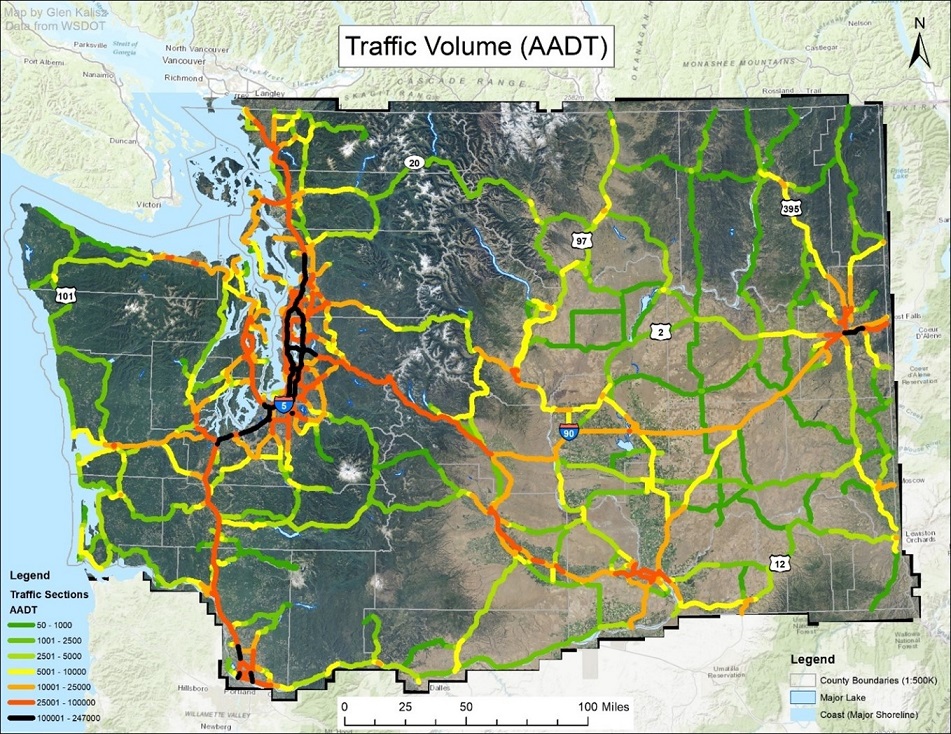

Most deer and larger animals can cross roads with low traffic volume (fewer than 2,000 vehicles per day), but these roads still pose a significant risk to smaller, slower animals. Such species are usually too small to be recorded as vehicle-related mortalities because they go unnoticed or are scavenged within hours of a collision. As a result, they are not well represented in carcass removal data.

Rural highways with moderate traffic volumes (between 3,000-10,000 vehicles per day) tend to have the highest rates of wildlife-vehicle collisions because animals still attempt to cross, but the frequency of traffic increases the likelihood they will get hit. Eventually, avoidance becomes the animals' main response to busy roads and those living on either side can become isolated from one another—this is known as the barrier effect. Roadways with traffic volumes greater than 10,000 vehicles per day are considered complete barriers to most species.

Isolated wildlife populations lead to weaker genetics over time due to increased inbreeding or decreased reproductive potential, resulting in the possible extinction of species. Recent studies indicate cougars on the Olympic Peninsula already suffer from genetic deficiencies, potentially because of the barrier effect created by I-5. Improving habitat connectivity supports stable wildlife populations and significantly reduces the chance of dangerous wildlife-vehicle collisions.

WSDOT prioritizes connectivity using a two-pronged approach

WSDOT uses Habitat Connectivity Investment Priorities to guide its two-pronged approach of addressing habitat connectivity by increasing the ability of animals to safely move across roads (by eliminating or reducing barriers) and reducing the number of wildlife-vehicle collisions. The HCIP ranks the state highway system, in one-mile segments, based on two categories:

- Ecological stewardship reflects a highway segment's overlap with the habitat ranges of select endangered or threatened wildlife, as well as its proximity to connected networks of habitat identified by the Washington Wildlife Habitat Connectivity Working Group. Other factors are also considered, such as traffic volume and nearby blocks of protected land.

- Wildlife-related safety prioritizes areas with higher carcass removal and wildlife collision rates.

Ongoing projects target locations most in need of habitat connectivity or reductions in wildlife-vehicle collisions. WSDOT also strives to incorporate structures to improve both wildlife crossing and fish passage within the footprint of other projects.

2022

- WSDOT and partners recorded over 20,000 safe wildlife crossings at the Snoqualmie Pass East Project area since the first stage of construction was completed

- WSDOT's US 97 Janis Bridge wildlife crossing project reduces annual deer-vehicle collisions by up to 90% near the vicinity of Tonasket in Okanogan County

- WSDOT removed 40,968 wildlife carcasses from state highways from 2018 to 2022

WSDOT aims to increase habitat connectivity and decrease wildlife-vehicle collisions

Habitat connectivity is how the landscape facilitates or impedes animal movement and other ecological functions. Roadways alter landscapes and can create barriers to these movements, which are crucial to survival for many species. Wildlife-vehicle collisions represent an ongoing danger to the traveling public and typically result in an animal's death. WSDOT is working to increase habitat connectivity and reduce these types of collisions.

Most deer and larger animals can cross roadways with low traffic volumes (fewer than 2,000 vehicles per day) without issue. Roadways with traffic volumes greater than 10,000 vehicles per day practically become total barriers to most species.

Isolated wildlife populations lead to weaker genetics over time and can result in extinction of species unable to adapt quickly to the change. Recent studies indicate

cougars on the Olympic Peninsula are suffering from genetic deficiencies, potentially because of the barrier effect created by Interstate 5, which sees up to 121,000 vehicles per day between Olympia and Oregon. Improving habitat connectivity supports stable wildlife populations and significantly reduces the chance of dangerous wildlife-vehicle collisions.

WSDOT prioritizes connectivity investments using two-pronged approach

WSDOT uses Habitat Connectivity Investment Priorities to guide its two-pronged approach of addressing habitat connectivity by increasing the ability of animals to safely move across roads (by eliminating or reducing barriers) and reducing the number of wildlife-vehicle collisions. The HCIP ranks the state highway system, in one-mile segments, based on two categories that reflect our two-pronged approach to habitat connectivity:

- Ecological stewardship reflects a highway segment's overlap with the habitat ranges of select endangered or threatened wildlife, as well as its proximity to connected networks of habitat identified by the Washington Wildlife Habitat Connectivity Working Group. Other factors are also considered, such as traffic volume and nearby blocks of protected land.

- Wildlife-related safety prioritizes areas with higher carcass removal and wildlife collision rates.

Wildlife crossing structures in Washington

Washington's first wildlife crossing structures were built in 1976 on Interstate 90, outside North Bend. Since then, WSDOT has constructed over two dozen wildlife crossings and has become a leader in habitat connectivity. Ongoing projects target locations most in need of habitat connectivity or reduction in wildlife-vehicle collisions and work to include wildlife crossing and fish passage structures within the footprints of other projects.

2021 (first year reporting in the GNB)

- WSDOT and partners recorded a minimum of 8,683 animal crossings in the Snoqualmie Pass East Project area in 2020 and 2021

- WSDOT's Butler Creek wildlife crossing project reduces wildlife-vehicle collisions by 81% in the area

- WSDOT's Janis Bridge wildlife crossing project reduces deervehicle collisions by 91% in the area

- WSDOT removed 41,151 wildlife carcasses from state highways from 2017 to 2021

WSDOT aims to increase habitat connectivity and decrease wildlife-vehicle collisions

Habitat connectivity is how the landscape facilitates or impedes animal movement and other ecological functions. Roadways alter landscapes andncan create barriers to these movements, which are crucial to survival for many species. Wildlife-vehicle collisions represent an ongoing danger to the traveling public, and typically result in an animal's death.

WSDOT is working to increase habitat connectivity and reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions. Watch this video to see animals using WSDOT's crossing structures.

Most deer and larger animals can cross roads with low traffic volume (fewer than 2,000 vehicles per day) without issue. These roads still pose a significant risk to smaller, slower animals, which take longer to cover the same distance. Such species are usually too small to be recorded as vehicle-related mortalities and are not listed in carcass removal data.

Rural highways with moderate traffic volumes (between 5,000-10,000 vehicles per day) tend to have the highest rates of wildlife-vehicle collisions because animals still attempt to cross, but the frequency of traffic increases the likelihood they will get hit. Eventually, avoidance becomes the animals' main response to busy roads and those living on either side can become isolated from one another—this is known as the barrier effect. Roadways with traffic volumes greater than 10,000 vehicles per day are practically complete barriers to most species.

Isolated wildlife populations lead to weaker genetics over time, and possible extinction of species unable to adapt to the change quickly enough. Recent studies indicate the cougars on the Olympic Peninsula are already suffering from genetic deficiencies, potentially because of the barrier effect created by Interstate 5, which sees up to 121,000 vehicles per day between Olympia and Oregon. Improving habitat connectivity supports stable wildlife populations and significantly reduces the chance of dangerous wildlife-vehicle collisions.

WSDOT prioritizes connectivity investments using two-pronged approach

WSDOT uses Habitat Connectivity Investment Priorities to guide its two-pronged approach to addressing habitat connectivity through increasing the ability of animals to safely move across roads by eliminating or reducing barriers and by reducing the number of wildlife-vehicle collisions. The HCIP ranks the state highway system, in one-mile segments, based on two categories that reflect our two-pronged approach to habitat connectivity:

- Ecological Stewardship, and

- Wildlife-related Safety

Ecological Stewardship

reflects a highway segment's overlap with the habitat ranges of select endangered or threatened wildlife, as well as its proximity to connected networks of habitat identified by the Washington Wildlife Habitat Connectivity Working Group.

Wildlife Habitat Connectivity

Working Group. Wildlife-related Safety prioritizes areas with higher carcass removal and wildlife collision rates.

Wildlife crossing structures in Washington

Washington's first wildlife crossing structures were built in 1976 on Interstate 90, outside North Bend. Since then, WSDOT has constructed over two dozen wildlife crossings and has become a leader in the habitat connectivity world. Ongoing projects target locations most in need of habitat connectivity or reduction in wildlife-vehicle collisions and work to include wildlife crossing and fish passage structures within the footprints of other projects.