Tacoma Narrows Bridge history - Community connections - Aftermath

Aftermath - A New Beginning: 1940 - 1950

Scandals, squabbles, and lawsuits gave way to the building of a sturdy, new Narrows Bridge—but it took almost a decade.

What's here?

- Gertie & The Media

- Scandal: Who was to blame?

- The FWA Carmody Investigation Board

- Impact on Tacoma and Peninsula residents

- The Money Side—Scandal, Squabbles & Lawsuits

- It Took Almost a Decade

- Building the Second (Current) Bridge

- Three Workers Died

- Completion of the Bridge, October 1950

Ruined Gertie: The collapsed 1940 bridge, WSDOT

Gertie and The Media

Shortly after the fall of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, radio reporters arrived at the scene. Carroll Foster and KIRO (Seattle) newsmen broadcast from the scene and from a plane circling above the site. They interviewed several people, including Senator Homer T. Bone.

"This is the most astounding sight I have ever witnessed in my lifetime," exclaimed Senator Bone.

Newspapers gave wide coverage to the spectacular event. So did national news magazines like Newsweek and Life. Since 1940, on the anniversary date November 7 various newspapers in the Puget Sound region print stories about the great collapse.

Grim faces of bridge builders as they view collapsed 1940 bridge. Left to right, Washington Toll Bridge Authority Secretary Patrick Winston; Acting Highway Director James Davis; Project Engineer Clark Eldridge; Chief Engineer Charles Andrew; U. of W. Professor F. B. Farquharson. The copyright in this image is the property of the Tacoma Public Library. Any additional copies or reproduction of this image are prohibited. All rights reserved

Scandal: Who Was to Blame?

"U.S. Money-lenders blamed by engineers for span crash"

That headline appeared in the Tacoma Times on November 9, 1940, two days after the collapse of Galloping Gertie. When reporters asked lead project engineer Clark Eldridge to explain why the Narrows Bridge collapsed, he could not hold back. He was angry.

Eldridge told the newspapers:

"The men who held the purse-strings were the whip-crackers on the entire project. We had a tried-and-true conventional bridge design. We were told we couldn't have the necessary money without using plans furnished by an eastern firm of engineers, chosen by the money-lenders." Eldridge and other state engineers had protested Leon Moisseiff's design with its 8-foot solid girders, which he called "sails." But, it was no use.

Public Works Administration officials said they knew nothing about a problem with the bridge's design. Soon, however, one of their own engineers broke the truth to the newspapers and the public.

Two months later, the scandal again made headlines: "BRIDGE EXPOSE BREAKS" bannered the Tacoma Times on January 11, 1941. This time, it became public that the PWA's own engineer had refused to approve the bridge when it was completed in July 1940. David L. Glenn, the PWA's field engineer on site in Tacoma, submitted a report warning of faults in design and refusing to recommend acceptance of the structure. But, the PWA accepted the bridge. So did the Washington State Toll Bridge Authority.

The PWA fired David Glenn two weeks after the story made headlines. Newspapers reported that he had been "relieved" of his position on January 25, 1941.

The FWA ("Carmody") Investigation Board

The State of Washington and the United States government both appointed boards of experts to investigate the collapse of the Narrows Bridge. The insurance companies established a "Narrows Bridge Loss Committee."

The Federal Works Administration appointed a 3-member panel of top-ranking engineers: Othmar Amman, Dr. Theodore Von Karmen, and Glen B. Woodruff. Their report to the Administrator of the FWA, John Carmody, became known as the "Carmody Board" report.

In March 1941 the Carmody Board announced its findings. Three key points stood out: (1) The principal cause of the Narrows Bridge's failure was its "flexibility;" (2) the solid plate girder and deck acted like an airfoil, creating "drag" and "lift;" and (3) aerodynamic forces were little understood and engineers needed to test all suspension bridge designs thoroughly using models in a wind tunnel.

The Board refused to blame any one person. The entire engineering profession was responsible, said the experts. They exonerated Leon Moisseiff. However, after November 7, 1940, his services were not in high demand.

The Carmody Board's report contained a statement by the Acting Commissioner of Public Works, J. J. Madigan, explaining the selection of consulting engineers for the Tacoma Narrows Bridge Project. It included the following statement: "In no instance did this Administration nominate, or express any preference for any particular individual, group or firm."

Clark Eldridge had a very different opinion. In his autobiography, Eldridge bluntly declares that Moisseiff and the consulting firm of Moran & Proctor, "associated themselves to secure the commission to design the Tacoma bridge. They went to Washington, called on the Public Works Administration and informed them that they could design a structure here that could be built for not more than $7,000,000. So when Mr. Murrow appeared asking for $11,000,000, our estimate, he was told $7,000,000 was all they would approve. They suggested that he confer with Mr. Moisseiff and Moran & Proctor. This he did, ending up employing them to direct a new design."

One month after the Carmody Board's report became public, Clark Eldridge decided he needed a career change. In April 1941 he resigned and took a job with the United States Navy on the island of Guam in the South Pacific.

Impact on Tacoma and Peninsula Residents

For Tacoma and the Peninsula, the collapse of the Narrows Bridge was a tragedy. The military lost its vital link between the Bremerton Navy Yard and the Army's installations at McChord Field and Camp Lewis for the duration of World War II. Merchants on both sides of the Narrows lost income from the retails trade between Pierce and Kitsap Counties. For many Peninsula residents the Narrows Bridge had been a lifeline, connecting their rural area to the commercial centers in Tacoma and even Seattle.

Disappointment ran high in Tacoma. "Bridge Price Too Low," wrote the Tacoma Times. Tacomans had lost the Narrows Bridge because it was "designed to fit a price." The newspaper blasted federal authorities for "an experiment in skimpiness." Just months earlier, the local media had praised Moisseiff's design as "graceful." Now they criticized it as "skinny."

Tacomans felt angry. The federal officials and eastern politicians who had restricted the funds for a Narrows Bridge had underestimated the region's need for the span. Nor did they appreciate the bridge's value to the people of the surrounding communities. But, Gertie's popularity proved them wrong. In its first four months, the bridge's revenues fully justified a $10 million bridge, one that would have been four lanes wide, strong, sound, safe-and still spanning the Narrows.

Restoring ferry service for cross-Narrows travelers got top priority. In 1938 the state had purchased Mitchell Skansie's Washington Navigation Company and two ferries. Immediately after the Narrows Bridge collapsed, officials moved quickly. By 6 o'clock the very next morning (November 8th), two ferries began steaming over the route made obsolete just four months before. By the end of the decade, when the current Narrows Bridge was completed, commuters were ready for the new span.

| Year | Vehicles Annual | Vehicles Daily Avg. |

|---|---|---|

| 1930 ferry | 171,993 | 471 |

| 1935 ferry | 165,724 | 454 |

| 1939 ferry | 205,842 | 564 |

| 1940 bridge | 265,748 | 1,661 |

| (July 1- Nov. 7) (avg. 66,437/mo.) | ||

| 1940 ferry | 144,587 | 396 |

| 1945 ferry | 480,009 | 1,315 |

| 1950 ferry | 593,871 | 1,627 |

| (Jan. 1 – Oct. 13) | ||

| 1950 bridge | 280,464 | 3,904 |

| (Oct. 14 - Dec. 31) | ||

| 1955 | 1,715,135 | 4,699 |

| 1960 | 2,269,570 | 6,218 |

| 1965 | 4,112,455 | 11,267 |

| 1970 | 7,724,860 | 21,164 |

| 1980 | 14,225,145 | 38,973 |

| 1990 | 24,299,145 | 66,573 |

| 2000 | 32,120,000 | 88,000 |

The Money Side—Scandal, Squabbles & Lawsuits

Galloping Gertie left a tangle of financial issues for the community and State officials to unravel. From insurance litigation to larceny, from salvage to successful funding, the money side of the collapse aftermath became a long chain of frustrating events.

The 1940 Narrows Bridge carried insurance spread among 22 different companies. The total insured value was $5.2 million, or 80% of its full value. When the bridge collapsed, the lives of some insurance men suddenly became very interesting.

Hallett R. French certainly became excited at the news of Galloping Gertie's demise. Insurance agent French had pocketed premiums on one of the State's policies and never reported the transaction to his company. He felt sure he'd never be found out. He was, of course, and went to prison for his bungled criminal effort.

Meanwhile, the State and the insurance companies became embroiled in settlement squabbles. On June 2, 1941 the insurance underwriters filed their report. They believed that the piers, cables, and towers could be salvaged and reused. They offered the State a settlement of $1.8 million. Three weeks later, on June 26, 1941 the State filed its claim. Except for the piers, said the State, the bridge was virtually a total loss, estimated at almost $4.3 million.

When the legal dust settled in August 1941, the two sides agreed on a settlement of $4 million. Considering the fact that the piers alone had cost $2.4 million of the bridge's total $6.4 million budget, the settlement amounted to a resounding victory for the State. Now the Toll Bridge Authority faced the problem of replacing the Narrows Bridge.

Unfortunately, the legal and insurance hassles had taken over 9 months to resolve. War intervened before funding could be secured and a new bridge started. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 disrupted the State's plans.

It Took Almost a Decade

Almost exactly a decade elapsed between first Narrows Bridge's collapse in November 1940 and completion in October 1950 of the Current Narrows Bridge. The insurance litigation was only the first of a series of events that slowed the work.

World War II also delayed efforts to replace the Narrows span. Salvage efforts began shortly after the November 7 failure of Galloping Gertie and continued to May 1943. Wartime shortages of steel and wire made them extremely valuable commodities. The State sold steel from the cables and the remainder of the suspension span as surplus.

Salvage of cables WSA, WSDOT records

In one of history's ironic twists, the salvage operation cost the State more money than was returned from the sale of surplus materials. By the time the State was able to build the bridge, it would have been cheaper to let the salvaged parts drop into the Narrows. The Toll Bridge Authority paid nearly $646,661 for the salvage operation. In return for the 7,000 tons of scrap steel the State received a meager $295,726. The operation posted a net loss of $350,933.

There were other reasons. In July 1941 Charles E. Andrew, Principal Consulting Engineer and Chair of the Board of Consultants for the Toll Bridge Authority, appointed Dexter R. Smith as chief design engineer to plan the new structure. By October, the state had a new design ready. The proposed 4-lane replacement bridge would cost about $7 million. And, it needed testing.

Testing the bridge design fell to F. B. Farquharson, Professor of Engineering at the University of Washington. Between 1941 and 1947, Farquharson studied the old span and the new proposed Narrows Bridge. The tests gave the State's bridge engineers confidence in their new design. The proposed new bridge would stand up to winds of 127 miles per hour.

Financing the second Narrows Bridge proved difficult. After World War II, many major construction projects competed for bond financing. The needs of Tacoma, Bremerton and other area residents were not high on financiers' priority lists.

By April 1946, revised designs for the Narrows Bridge were approved, with a projected cost of $8.5 million. But, steel was in short supply in the immediate post-WWII years. Also, the State had difficulty arranging for insurance for the bridge. Final designs were prepared, but not until August 1947 was the State able to request bids for the new bridge. By this time the cost had gone up. The price tag for construction was one-third more than the Toll Bridge Authority estimated-$11.2 million. The final construction cost estimate, made just prior to the bond issue, reached $13,738,000.

The tide turned when Pierce County contributed $1.5 million to a bond guarantee fund.

In December 1947 the Toll Bridge Authority offered a bond issue of $14 million. Revenues from tolls would pay for the bonds. Finally, on March 12, 1948 State officials completed bond financing. In the next two weeks contracts for building the bridge were awarded. Now, too, steel was available. Events began to move quickly.

Building the Second (Current) Narrows Bridge

Bethlehem Pacific Coast Steel Corporation and John A. Roebling Sons Company won the construction contracts for the replacement Tacoma Narrows Bridge. In June 1948 construction began. It took 29 months to complete the Current Narrows Bridge.

The workmen who built the great bridge braved the dangers of "high steel" work. They suffered during one of the coldest winters on record.

Three Workers Died

Three men lost their lives during construction of the current Narrows Bridge. Fellow workers honored their sacrifices. In the traditional token of respect, the crew quit work for the day and went to downtown Tacoma to hold a wake.

Workers faced the greatest dangers during the deck construction phase. Two of the three men who died were steelworkers helping to build the deck.

- Robert E. Drake, May 24, 1948

First to lose his life was carpenter Robert E. Drake. Drake worked for Woodworth Company. He and his fellow workers had been busy at the west anchorage. On May 24th Drake happened to be in the wrong place at the worst possible moment. He stood below a derrick just as a cable broke, sending the boom crashing down on him. - Glen "Whitey" Davis, date unknown

One of the ironworkers who helped build the deck was Glen "Whitey" Davis. He and Earl White worked steel on the same crew. During our recent interview with White, he grimly recalled Davis' death.

"He and I were real close friends. We had finished the deck and were starting to load timbers for the deck that the cement trucks would drive on. I had swung a big load of timbers in to him. When he stepped, he missed and went all the way down. God, when he hit, it sounded like an artillery piece went off."

- Lawrence S. (Stuart) Gale, April 7, 1950

It was a Friday afternoon. Stuart Gale was working on deck construction, helping to connect trusses in the support system. Fellow ironworker Earl White remembers the tragedy:"Stuart Gale died when they were working on the sections down below deck, where the diagonal and bottom chords were hooked together. These sections had temporary welds on them that were put on in the shops. So, they had swung this one section in, and Stuart Gale looked, and he called up to the young foreman, Danny Lowe. He said, "These welds don't look very good down here." It was Gale's first day on this part of the job, connecting the roadbed. So, Danny said, "Well, Gale, they've been holding all the way across. We haven't had no problem." A second time Gale hollered up. And, Danny said, "Cut 'er loose." And, when Gale did, well, 40 ton of iron and him went in the hole. You see, a safety net wouldn't have stopped him. They'd have caught Whitey Davis. But, they wouldn't have caught Gale and 40 ton of steel. He'd have gone right through. Danny was really hurt over this. He could never live that down."

Stuart Gale was 36 years old. They held a memorial service on a boat floating beneath the cold steel of the unfinished deck. Gale's wife and 3-year old daughter sat quietly. At the end, Mrs. Gale rose to her feet and cast a flower wreath onto the swirling waters of the Narrows.

Flower-covered Narrows Bridge on float in the Daffodil Festival parade in Tacoma, April 1950

Completion of the Bridge, October 1950

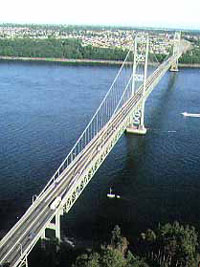

On October 14, 1950 opening day celebrations capped the long process to build Galloping Gertie's replacement. Final cost for the bridge, reported by Charles Andrew (as of June 30, 1952), stood at $14,011,384.28.

The new span, nicknamed "Sturdy Gertie" by local promoters, was indeed sturdier than its predecessor. Wider (to carry 4 lanes of traffic), heavier, and stronger, the 1950 Narrows Bridge signaled a new era of suspension bridge design. The span was a landmark of aerodynamic bridge engineering.

Souvenir booklet for 1950 opening celebration WSDOT

Aerial view of 1950 Narrows Bridge WSDOT