Tacoma Narrows Bridge history - Stories - The 1940 Narrows Bridge

People of the 1940 Narrows Bridge

Engineers, designers, professors, and the workmen who built the 1940 Bridge.

What's here?

- Elmer Hayden

- Clark Eldridge

- F. Burt Farquharson

- Leon Moisseiff

- Murrow, Lacey V.

- The Workers Who Built the 1940 Narrows Bridge

- Workman: John Adolfson

- Workman: Tom "Pinetree" Colby

- One Woman: Marie Guske

Assembling the catwalk, 1949 WSDOT

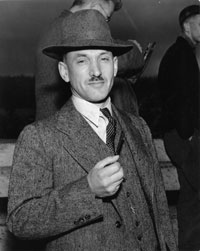

Elmer Hayden (1868-1938)

Elmer Hayden (1868-1938)

Elmer Maxwell Hayden's handprint remains on the first Tacoma Narrows Bridge. Mr. Hayden was senior partner in the law firm Hayden, Metzger, & Blair, which provided legal counsel necessary for the bridge to become reality. Tirelessly working behind the scenes on the behalf of his community, Mr. Hayden is credited with spending a dozen years as voluntary legal counsel to promote creating a new link between Tacoma and the Key Peninsula.

Mr. Hayden's support for building a Tacoma Narrows Bridge was far-reaching. Providing legal support to county commissioners, authoring legal documents, appearing before the state's Supreme Court, serving on committees and on the Chamber of Commerce's Board of Trustees, Mr. Hayden used every venue available to him to promote and support the bridge concept.

"Mr. Hayden was one of the original subscribers to the Narrows bridge working fund created in 1927. He was a member of the Narrows bridge committee since it was organized," according to a story printed in the Tacoma News Tribune after his death in 1938. "Without doubt, Mr. Hayden has contributed more to the advancement of the Narrows bridige (sic) project than any other individual," the article continued.

Mr. Hayden was born in Indiana on Oct. 25, 1868, and died at the age of 69 in Tacoma on August 16, 1938.

Clark Eldridge, Bridge Engineer, 1940 WSDOT

Clark Eldridge (1896-1990)

From modest beginnings in the small western Washington town of Lake Stevens, Clark Eldridge became one the state's most noted bridge engineers.

Bright, energetic, and dedicated, Eldridge completed engineering studies at Washington State College in 1920. Over the next fifteen years, he distinguished himself in the Seattle City Bridge Engineer's office. Then, in 1936 Eldridge joined the State Highway Department. The forty-year old engineer found himself designing two of the state's most colossal bridges, the Lake Washington Floating Bridge and the Tacoma Narrows Bridge.

From the outset, Eldridge considered the Tacoma Bridge "his bridge." The Highway Department had challenged him to find money to help build it, and he did. His boss, State Highway Director Lacey V. Murrow, took Eldridge's design and cost estimates to the Public Works Administration in Washington, D. C. in the Spring of 1938.

Federal officials decided that Eldridge's plan was too expensive. They required the Washington State Toll Bridge Authority to hire noted suspension bridge engineer Leon Moisseiff of New York as a consultant. Moisseiff redesigned the structure, and the Tacoma Narrows Bridge moved forward. Eldridge supervised construction.

In November 1940 barely four months after the bridge opened, Eldridge received the telephone call that changed his life.

"I was in my office about a mile away when word came that the bridge was in trouble," he wrote later. He drove to the bridge, but had to be lead off the leaping roadway by a fellow engineer. "There, we watched the final collapse," Eldridge sadly noted.

Eldridge stayed with the project only a few more months. In April 1941 he took a job with the U. S. Navy on Guam. Soon, the start of World War II and a Japanese attack landed Eldridge in a prisoner of war camp for the duration of the war.

After the war, Eldridge returned home and worked as a consulting engineer until his retirement in 1970. But, "retirement" was only an official departure from public employment. Eldridge worked almost tirelessly until his death two decades later.

Clark Eldridge's memories of Galloping Gertie remained tinged with sadness. As he wrote in his memoirs, "I go over the Tacoma Bridge frequently and always with an ache in my heart. It was my bridge."

The 1950 Narrows Bridge that rose in its place must have been some consolation, however. The bridge we cross today stands on the piers that Eldridge designed. And, with its deep Warren stiffening truss deck, it closely resembles the bridge Eldridge designed before fate fell across his path.

Frederick Burt Farquharson, 1940

Frederick B. (Burt) Farquharson (1895-1970)

Few engineering professors leave a mark in their profession as prominent as the one made by Frederick Bert Farquharson. As a professor of civil engineering at the University of Washington for most of his career, 1925 to 1963, Farquharson pioneered aerodynamic studies of the 1940 and 1950 Tacoma Narrows Bridges.

At the time, wind tunnel testing for aerodynamic forces on bridges was in its infancy. Farquharson began by applying basic information developed in the late 1930s for aircraft design.

Born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1895, Farquharson served in World War I with the Canadian army and the Royal Air Force. But, the Germans captured him in 1917 and Farquharson spent the last 15 months of the war in a prisoner of war camp.

Upon returning to the United States, Farquharson attended the University of Washington, where he graduated in 1923. After two years working for the Boeing Company, the able young engineer accepted an offer to join the UW faculty. He went on to head the University's Engineering Experiment Station and became a world-recognized authority on aerodynamic testing for bridge design.

Farquharson stood on the 1940 Tacoma Narrows Bridge the day it collapsed. He intently monitored its behavior, snapped photos, and took motion picture film of the disaster. Farquharson's movie remains a "classic" that is viewed by engineering students around the world.

In the 15 years that followed, Farquharson's pioneering aerodynamic studies helped build the 1950 Narrows Bridge and other suspension spans around the world. He retired from the University of Washington in 1963. Farquharson died at home on June 17, 1970 at the age of 75.

Read his fascinating experience of Galloping Gertie's collapse.

Leon Moisseiff, 1940 WSDOT

Leon Moisseiff (1872-1943)

The lead designer of the 1940 Tacoma Narrows Bridge, Leon Salomon Moisseiff, was at the peak of his engineering profession when the ill-fated span collapsed into the chilly waters of Puget Sound that November day.

Born in 1872 in Latvia, Moisseiff at the age of 19 moved to New York with his parents. The talented young engineer graduated from Columbia University in 1895. Only three years later, he joined the New York City Bridge Department. Moisseiff helped design and build some of the world's largest suspension bridges, beginning with the 1909 Manhattan Bridge over the East River. He published an article about his work on the Manhattan Bridge that promptly won him national acclaim as the leading proponent of the "deflection theory," which he introduced from Europe.

Moisseiff's elaboration of the "deflection theory" laid the groundwork for thee decades of long-span suspension bridges that became lighter and narrower. These bridges were not only more "graceful" and beautiful to the public and to engineers at the time, they also were cheaper to build, because they used far less steel than earlier spans. Moisseiff became a private consultant and was involved in the design of almost every major suspension bridge built in the 1920s and 1930s.

The culmination of Moisseiff's work was the 1940 Tacoma Narrows Bridge. He called it the "most beautiful" bridge in the world. Unfortunately, Moisseiff had entirely overlooked the importance of aerodynamics in his bridge designs. As they became lighter and narrower, they became more flexible and unstable.

When Galloping Gertie collapsed, Clark Eldridge publicly pointed the finger at Moisseiff. Eldridge believed that Moisseiff unethically approached the Public Works Administration and convinced them to require Washington State to hire Moisseiff, to review the design that Eldridge had prepared.

Moisseiff's other professional colleagues exonerated him. Still, the disaster effectively ended his career. His health had been compromised since 1935, when he suffered a heart attack. He died at age 71 on September 7, 1943, just three years after failure of his "most beautiful" bridge.

In recognition of his contributions to the engineering profession, the American Society of Civil Engineers established the Moisseiff Award fund.

Lacey V. Murrow, Highway Director, 1940 WSDOT

Lacey V. Murrow (1904-1966)

To many people Lacey Murrow seemed to stand in his younger brother's shadow. He was the older brother of Edward R. Murrow, the noted pioneer journalist, radio and television news commentator, and one-time head of the U. S. Information Agency. But, each man made his own unique contributions to society and received many accolades during his lifetime.

Born in Greensboro, North Carolina in 1904, Murrow grew up with his brothers Dewey and Ed in Blanchard, Washington. The Murrow brothers attended Washington State University. Lacey graduated with a B. S. in Military Science in 1926, and later in engineering in 1935.

Murrow had worked for the State Highway Department intermittently beginning in 1919, then he moved steadily into positions of higher responsibility. In 1933 Murrow began an eight-year term as Director of the State Highway Department. It proved a turning point in his career, and in the history of bridges in Washington.

In 1937 Murrow served also as Chief Engineer for the State Toll Bridge Authority. He became a forceful advocate for a floating bridge across Lake Washington, which was completed in 1940. The same year, Murrow oversaw the department's completion of the first, and ill-fated Tacoma Narrows Bridge.

Prior to America's entry into WWII, Lacey accepted a commission as a Lt. Col. in the Army Air Corps and resigned as Director of Highways in September 1940. Before the war his favorite sport had been flying. In the war, it became his profession. From 1940-46 he served as a command pilot, winning military honors including a presidential citation with four cluster decorations, the Legion of Merit, the Order of the British Empire, and the Croix de Guerre. On April 27, 1948, Murrow was promoted to Brigadier General in the Air Force. He served in Korea, Japan, and the United States before retirement.

From 1954 until his death, Murrow lived in Washington, D. C. and worked for Transportation Consultants, Inc., serving most of those years as the firm's President.

A life-long smoker, Lacey Murrow, like his brother Edward, began suffering from lung cancer in the early 1960s. He underwent an operation shortly before his brother's death from the disease in 1965. Little more than a year later, in December 1966 at the age of 62, Lacey was found shot to death in his room at the Lord Baltimore Hotel, a 12-gauge shotgun propped against the bed.

Soon after Murrow's suicide, the Washington State Legislature passed a resolution requesting that the State Highway Commission re-name the first Lake Washington Floating Bridge in his honor. The Commission agreed, and in March 1967 paid tribute to Murrow, declaring, "this notable engineering achievement received world-wide recognition for its pioneering of a new concept in over-water structures."

Workmen setting tower base plate, August 1939 WSDOT

Diver Johnny Bacon, a 15-year veteran bridge worker, takes a break in his 200 lb. diving suit, May 1939

The Workers Who Built the 1940 Narrows Bridge

"Boomers" were the most experienced workers. "Boomers" is what they called bridge workmen who traveled across the country, following one large bridge construction project to the next. They worked on bridges their entire careers. Often, they learned the skills from their fathers, who had learned from their fathers. "Boomers" tended to stick with the largest bridges when possible. These men formed the nucleus of the crew, lending their expertise to help guide the hands of inexperienced local workmen.

In early May 1940 workers laying concrete for the roadway immediately noticed when the bridge began its soon-famous waves. Most likely, it was one of the "boomers" who dubbed the bouncing span, "Galloping Gertie."

The pay for workers on the first Narrows Bridge averaged $1.35 per hour. Men worked a 40-hour week, Monday through Friday, with Saturday and Sunday off. But, for those five days, work proceeded around the clock. Crews changed shifts at 6 a.m., 2 p.m., and 10 p.m. In the months before the bridge's completion, the workforce included about 225 men, plus a couple dozen engineers and support staff.

A "Boomer": John Adolfson

One "boomer" on the first Narrows Bridge was John Adolfson. By the time the 1940 Narrows Bridge neared completion, Adolfson had been a "boomer" for some 20 years. He was 48 years old and married, with one son. Before the Narrows job, he worked in San Francisco on the Golden Gate Bridge and in New York on the George Washington Bridge.

Adolfson often worked at great heights. Walking a single cable (with hands on a second cable for balance) some 300 feet above the Narrows was a perilous part of his daily job. Dangerous and difficult construction problems were routine to "boomers" like Adolfson. He once told a reporter, "You get over thinking about falling after you've been up there a few years."

After the Narrows Bridge opened to the public in the summer of 1940, John Adolfson and his family headed off for his next job, located in Hawaii. He was there helping to build dry docks at the Naval base in Pearl Harbor when the Japanese attacked on December 7, 1941. His fate is unknown.

Tom "Pinetree" Colby WSDOT - Click to enlarge image

Workman: Tom "Pinetree" Colby

How does a Wyoming sheepherder get to the Tacoma Narrows Bridge? We may never know the full story, but Tom "Pinetree" Colby was the guy. Born to a sheep-herding family in Wyoming in 1912, Colby eventually left for California. He learned the riveting trade in Sacramento and helped build the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco.

He turned up in Tacoma in 1939 when the steel towers for Galloping Gertie began to rise off the piers. He helped build the 1950 Narrows Bridge too. Colby quickly earned respect for his genial personality, broad smile, and skill with hot rivets.

After the deck crew assembled the truss-deck system, the riveting gangs followed. A typical crew was four men. A "heater" heated and tossed the red-hot rivets, or sent them through a pneumatic tube if the distance was too great. A "catcher" caught and placed the rivets. A riveter worked a rivet gun on one side of the cold steel to be joined. On the other side stood the "bucker-up," who used an air jack or hand tool to back-stop the hot rivet.

Workers caulking cable band with lead wool, May 7, 1940 WSDOT

Fellow worker Joe Gotchy described "Pinetree" as a "riveter's bucker-up extraordinary." Colby squeezed into the most uncomfortable spots at odd body angles time and again, enduring the rivet gun's loud hammering, always coming up for fresh air with that big, toothy grin on his face.

Gotchy called Colby "unforgettable" and "homely." But, the rivet man's skill and unfaltering smile, even in the hardest conditions, won the admiration and friendship of his co-workers. "Here is a diamond in the rough," Gotchy declared.

Marie Guske WSDOT

One Woman: Marie Guske

One woman worked on the 1940 Tacoma Narrows Bridge. Marie Guske was her name. Marie was the secretary to lead project engineer Clark Eldridge.