Tacoma Narrows Bridge history - Stories of the current Narrows Bridge

People of the current Narrows Bridge, 1950 to present

They did the work to finish the bridge, and their inheritors keep it in top shape today—Earl White and Joe Gotchy.

What's here?

Jackson Avenue view of the current Tacoma Narrows bridge

Compacting main cable, 1950 WSDOT

Steel workers completing the deck of the current Narrows Bridge, Photo courtesy of Earl White

Driving the last rivet, 1950 WSDOT

Bridge workers - Nerves of steel

"Nerves of steel" is a cliche, but it best describes the ironworkers on the 1950 Narrows Bridge. Daily they risked serious injury or their lives.

Like their predecessors on the 1940 bridge, the workmen who built the current Tacoma Narrows Bridge were strong, hard-edged, quick-witted, and often colorful. "Bridge workers are a different breed of cat," says Earl White, a steel man on the 1950 bridge.

They were a rough group. They loved crude humor and practical jokes. The difficult, dangerous work bonded them. They didn't always get along, but there was a sense of camaraderie. They would "give you the shirt off their backs," says White.

Steelworkers had a distinct hierarchy.

Whether you were a local from the union hall or a "boomer," it prescribed the division of labor at the building site. "Bridgemen" were welders (who positioned and welded steel) or rivet men (who heated, caught, or drove rivets). Apprentices, or "punks," assisted the bridgemen, fetching needed items, sometimes trying their hand with the tools, and observing.

Usually, an apprentice became a regular bridgeman after 2 or 3 years. A first-level supervisor, called a "pusher," supervised several groups of bridgemen and apprentices. These levels operated under the watchful eye of a "walkin' boss," who reported to the construction supervisor.

Three workers lost their lives during construction of the current Narrows Bridge.

They were Robert E. Drake, carpenter at the west anchorage, May 24, 1948; Lawrence S. (Stuart) Gale, iron worker building the deck, April 7, 1950; Glen "Whitey" Davis, iron worker building the deck (date unknown).

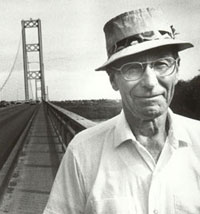

Earl "Whitey" White (1921 --)

Earl "Whitey" White is a tough guy. And, he's a survivor. He "worked iron," for 43 years, on all kinds of structures.

He grew up in Puyallup and settled in Tacoma. White and his wife, Penny, raised two sons on the modest income of a welder and heavy construction steel worker.

White was born in 1921 in Wibaux, Montana. His parents moved to Puyallup when he was 3 years old, and there he graduated from high school in 1939. After a year in the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps), young "Whitey" had enough money to take a welding course. By 1940 he started welding at the Tacoma Shipyards. When World War II came, he decided to join the U. S. Marines. At the age of 22 in 1943, he went off to fight the war in the Pacific with the 5th Marine Division.

Back home after the war, White again took up "working iron." From 1946 until he retired in 1989, he helped build hundreds of steel structures around Tacoma and the Northwest, including many of the buildings on the Tacoma tide flats, high-rise office buildings, radar towers, dams, and most memorable of all, the 1950 Tacoma Narrows Bridge.

"Working iron" is hard physical labor. You get busted up a lot. White has narrowly missed death and had parts of his body mangled. He has had his "lunch box brought home" by a co-worker three or four times, meaning he went to the hospital from an injury. One injury laid him up for 22 months—almost 2 years.

On the Narrows Bridge from 1948 to 1950 White worked on the suspended structure, putting up the towers, cable spinning, and building the steel deck. The work was hard and conditions sometimes harsh. He saw friends die. With a somber, steady voice he talks about the day that his buddy, Whitey Davis, "went in the hole," and "hit the water with a sound like an artillery piece going off." He saw another ironworker "go into the hole with 40 ton of steel." He suffered the severe winter of 1949-50, when bitter winds, lashing rain, swirling snows, and a catwalk frozen solid with ice made work miserable for weeks.

White faced danger routinely every day while helping to build the 1950 Narrows Bridge. He and the other bridge men worked hundreds of feet over the Narrows without "tying-off" their safety lines. They felt safer working unfettered. They had no safety net. But, working at great heights is not for everyone. "I've seen guys who've worked iron all their life freeze," says White.

"Bridge workers are a different breed of cat," says White. "They're a pretty rough bunch. They worked hard, they lived hard. And, damn near every one of them would give you the shirt off his back."

You could say that about retired 82-year old bridge-builder, ironworker Earl "Whitey" White too. And, he'd take it as a compliment.

Here are excerpts from our interview with Earl White:

"When they started the Narrows Bridge, I went out there and proceeded to help build the bridge for the next 29 months. I worked out of Local 114 Ironworkers Union; went to work for Bethlehem Steel. I think I earned $1.75 an hour.

"I started on the job when they were setting the tower base plates. I worked on compacting the cable, building the deck, and all the rest.

"We had a lot of boomers on the bridge. We brought in many gangs of riveters. Hot shot riveting gangs would come from 'Frisco and the East Coast. We had 'em from all over the world. Some would stay and some would get a paycheck or two and take off.

"That winter (1949-50), the catwalk froze solid. Guys would take a few steps and their feet went right out from under them. When I got up to the top of the tower, I chipped ice off the cable saddle (this was during cable spinning). You may not believe this, but that ice was 1-1/8 inches thick.

"I suffered more on the Narrows Bridge than working on radar towers in the winter in Cutbank and Havre, Montana. It was just so cold and wet. It was bitter cold. Snow was drifting, wind was blowing. It was miserable. One time during the night, the wind kept picking up. It was over 100 miles an hour. That was the scariest night I ever put in in my life.

"When we'd start up that cable, I could almost put a paint mark where I took the next step, when that wind would come around that point and hit you right square in the face, just like "smack." All of a sudden, you leaned forward, because from then on you were going to lean forward. Then, sometimes I'd go up that catwalk in the morning. It would be socked-in solid, you couldn't see your hand in front of your face. You know how fog sets in. You'd get up above that 500-foot level, and all of a sudden your head come up above those clouds and you felt like you're in heaven. You'd see the mountain tops sticking out, just a little bit of them. It was like being in an airplane up above the cloud level. It was an eerie feeling sometimes.

"Working on the bridge, you'd see pods of killer whales come through. Then, there comes a ball of herring 200 feet across, looked like a big basketball underneath the water. Then you'd see the salmon, swimming through, hitting them with their tails, then they'd come back and eat 'em. Once in a while, you'd see a seal after the salmon. They, the boats would come. When the boats saw the seagulls, they'd come up to get a supply of herring for fishing.

"The wives had a pretty hard time too. Like that day Whitey Davis fell off. We just had radios in those days. Well, I was known as "Whitey" White—and I had light hair then too. One gal called my wife and told her, "Whitey fell off the bridge." We closed down the bridge and headed to town and held a wake. She found out in the meantime it wasn't me. But, for a long while all she had was, "Whitey went into the hole." Then, this gal calls up my wife and says it wasn't Earl. I got home about midnight. I wasn't very popular. She'd had my lunch bucket brought home three or four times. You get busted up quite a bit. Once, I was off about 22 months.

"I've seen guys who've worked iron all their life freeze. On any given day, just freeze. In those days we never tied off, like now. We had our ropes on—you had to wear this. But, we never tied off, because about the time you tie-off you have to make a quick move, something's gonna happen. We just didn't feel safe.

"Bridge workers are a different breed of cat, I guess that's how I'd describe 'em. I had some wonderful friends in the ironworkers, but there's only about two of 'em I've ever brought into my home. They're a pretty rough bunch. They worked hard, they lived hard. And, damn near every one of them would give you the shirt off his back.

"One Christmas I'd been out of work. A load of iron bars knocked me, and I come down and smashed my elbow all to hell. Still, I can't straighten it out. That Christmas things were tough, real tough. Come Christmas, three of the ironworkers come up to the door, and they had a turkey, everything you could think of for a Christmas dinner, turkey, wine, cranberries. That's the kind of guys they were.

Earl White, steel worker, 1950

Joe Gotchy (1903-1994)

Quite a few men helped build both Tacoma Narrows Bridges. One who has left his mark on history is Joe Gotchy.Gotchy at the age of 87 published a personal account of that experience. The book, Bridging the Narrows (Gig Harbor Peninsula Historical Society, 1990), is an important source of information about the construction of the two bridges and the people who worked on them.

On the two spans Gotchy handled various jobs. He supervised concrete mixing and operated cranes during pier construction. On the 1950 bridge, Gotchy worked as an operating engineer helping to build the towers, then building the deck from the Gig Harbor end toward mid-span with the west side deck crews.

Joe Gotchy loved bridges. Born on February 3, 1903 in Bothell, Gotchy grew up in rural Thurston County. He worked on bridges all over Washington State. A high school dropout, he lacked formal education. But, he read avidly and became a life-long learner.

In his career, Gotchy was an operating engineer, an ironworker, and a lumberjack. He cared deeply about his family, fellow workers, his community, and the environment. Gotchy and his wife lived in Gig Harbor in his last 23 years. He passed away on December 3, 1994.

In 1992 at the age of 89 Gotchy helped gather signatures on a petition to convince the State to provide the funding for a new Narrows Bridge that would ease traffic congestion. When that new bridge opens in 2007, Joe Gotchy will be one of the very few who have helped build, directly and indirectly, all 3 Tacoma Narrows Bridges.

Joe Gotchy, GHM, NB-080