Tacoma Narrows Bridge history - The bridges as art

"Most beautiful in the world" – Art and the 1940 Narrows Bridge

The making of a classic Modernist span.

What's here?

- The art of suspension bridges

- Architecture & art in the "Machine Age"

- Suspension bridge architecture in the 1930s

- "Most beautiful in the world"

- Artistic design elements

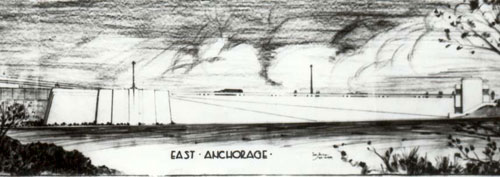

Artist's sketch of 1940 Narrows Bridge with toll plaza WSDOT

The art of suspension bridges

Bridges are graphic expressions of American culture. Their unique purpose and forms have moved painters and poets, as well as architects. One great poet, Walt Whitman, extolled American bridges when he wrote, "The Earth be spanned, connected by network. The lands be welded together."

What do we mean by "art" and "aesthetics" of suspension bridges?

Bridges look the way they do for very definite reasons. In part, they reflect the historical period when they were created. The 1883 Brooklyn Bridge had massive masonry towers. The 1940 Tacoma Narrows Bridge had tall, slender steel towers. That difference is due to more than engineering or technology advances.

Aesthetics is about "beauty." It's about what makes an object visually pleasing, or not. The appearance of a bridge concerns engineers as much as its structural mechanics. In discussing the "aesthetics of suspension bridge design" we are looking at its appearance, its style, if it is beautiful (or not), and the meaning of beautiful (what makes it beautiful or ugly).

The engineers who designed the great suspension bridges used their individual sense of architectural design, artistic taste, and creative style. The artistic features of a bridge are expressed in its materials, proportions, balance, lines, ornamentation, and relationship to the environment. Every line on the 1940 Narrows Bridge had both a structural-technical purpose, as well as an aesthetic impact.

Architecture & art in "the Machine Age"

In the 1920s American wealth and living standards rose rapidly. This was the new age of airplanes, cars, mass-produced (therefore more affordable) products, and nation-wide radio networks. People took a keen interest in the arts. There was much public debate about the design of buildings and bridges, both their appearance and their relationship with the surrounding environment.

America enjoyed the robust youthfulness of its rising wealth and the greatness of its growing technological power. Even after the stock market crash of 1929 and the hard times of the Great Depression that followed, the dream of greatness persisted. Skyscrapers came to symbolize the strengths of American civilization. The soaring towers represented America's vision of greatness, efficiency, elegance, power, courage, and even rebirth.

Skyscraper aesthetics played a significant role in the development of architectural styles in the 1920s and 1930s. The skyscraper dominated our urban environment by the 1920s. The influential architect Louis Sullivan designed taller and taller buildings, emphasizing the steel skeleton frame as of major importance in the skyscraper's appearance. Sullivan spoke of "the force and power of altitude" and "the rising in sheer exultation" of these immense buildings.

Empire State Building, a classic Art Deco skyscraper from the early 1930s

The "Frozen Fountain" was a conscious design metaphor for skyscraper designers. Claude Bragdon in his 1932 book, The Frozen Fountain, said, "In the skyscraper, both for structural truth and symbolic significance, there should be upward sweeping lines to dramatize the engineering fact of vertical continuity and the poetic fancy of an ascending force in resistance to gravity—a fountain."

The towers of New York's largest suspension bridges soared as high or higher than many skyscrapers. Consciously or unconsciously, designers of suspension bridge towers were paralleling efforts by designers of the tallest office towers.

In the "machine age," the 1920s and 1930s, architectural styles made significant shifts. The "machine age's" new synthesis of beauty and use distinguished the "modernist" trend. The objectives of design, declared one social commentator, were "Efficiency, economy, and right appearance." Design tastes preferred new materials like steel, chrome, sheet metal, and plastic.

The "modern" style of the 1930s was spare, clean, direct, pure, and simple, with no embellishments, no extra decorative detail. Style employed the subtle repetition of shapes and proportions. In architecture designers of the new forms emphasized symmetry and simple lines, geometry, energy, texture, light, and color.

Art Deco influences became increasingly evident in popular tastes. The Deco design movement affected everything from skyscrapers, airplanes, and cars, to radios, furniture, and kitchen appliances—and bridges. Many Deco buildings and other structures have "streamlined" curves and geometric patterns. For example, New York's great Empire State Building, Chrysler Building, and Waldorf Astoria Hotel (all completed in the early 1930s) incorporated the terraced or stepped pyramid as the dominant form. In the case of skyscrapers, there was also a practical reason. City zoning codes required setbacks to allow more natural light onto streets and sidewalks.

Streamlining affected structural designs, including suspension bridges. Smooth, flowing lines with an "aerodynamic" look were dramatic and economical. Streamlining gave structures both solidity and dynamic strength. The rapid growth of the airline and automobile industries coincided with a popular fascination with speed. Streamlined airplanes and cars became the most conspicuous symbols of the new "machine age."

The streamlined ferry Kalakala plied the waters of Puget Sound as a floating example of Art Deco transportation in our area. Built in 1935, the Kalakala held the honor of making the very last ferry run across the Narrows on July 2,1940.

Suspension bridge architecture in the 1930s

The late 1920s and 1930s saw great long-span suspension bridges built across the country. This reflected several important developments:

(1) innovations in engineering theory and practice, especially the "deflection theory" as applied by bridge designer Leon Moisseiff;

(2) improvements in materials, especially the introduction of high strength steel;

(3) the broader society's demands for more bridges and beautiful bridges, spurred by the rapid rise of the automobile in our lifestyles.

Suspension bridges became longer, lighter, and narrower. During this period, popular tastes in architecture favored more "graceful" bridges. "Graceful" or "elegant" spans were achieved in the public's eye by "lightness" and "slenderness." At the same time, in the wake of the Great Depression the public and the government wanted more efficient and less expensive bridges.

In other words, lighter, and narrower bridges were theoretically sound, they were cheaper to build, and they were more beautiful.

By the early 1930s, suspension bridge engineering design was summarized in these elements: The towers deserved the "best aesthetic treatment" for the public's eye; the bridge deck should be visually simple and structurally flexible.

"Most beautiful in the world"

"The most beautiful in the world." That's how engineer-designer Leon Moisseiff described his 1940 Tacoma Narrows Bridge. The statement represents much more than one engineer's opinion about his own work. Moisseiff's words reflect important architectural design trends and artistic tastes of the 1930s, as well as three decades of suspension bridge design.

Artist's sketch of 1940 Narrows Bridge WSDOT

Moisseiff cared deeply about bridge aesthetics. Bridge designs, he said, needed to be "safe, convenient, economical in cost and maintenance and at the same time satisfy the sense of beauty of the average man of our time." Moisseiff believed that engineers should try "to develop the beauty of their structures" by emphasizing "the essential, to interrupt rhythmically the monotonous and to indicate the minor importance of the auxiliary . . . and attain the pleasure of good form." Bridge designers, he said, should "search for the graceful and elegant."

The 1940 Tacoma Narrows Bridge, designed by Moisseiff in 1938, was a classic modernist span. Its Art Deco and streamlined features place it solidly in the artistic design trends of the 1930s.

Artistic design elements of the 1940 Narrows Bridge

It is important to remember that the 1940 Narrows Bridge had both structural-technical purposes, as well as an aesthetic impact. Since the turn of the 20th century, the designers of narrower, more flexible suspension bridges also sought to achieve a "graceful" artistic appearance. The 1940 Narrows Bridge, with its slim towers, shallow stiffening girder and Art Deco-influenced anchorages, became the epitome of "grace" and artistry in bridge design.

The various descriptions of the 1940 Narrows Bridge convey a distinct, artistic impression. Observers called the bridge "Galloping Gertie," and referred to the span as "her" or "she." This feminine span was "slender," "ribbon-like," "elegant," and "graceful."

The geography of the Narrows offered a unique design challenge. Here, high bluffs topped by tall evergreens straddled each of the narrow passage. The site clearly demanded an epic, even poetic, design.

The Narrows Bridge became the ultimate embodiment of Moisseiff's deflection theory, aesthetically, mathematically, and economically. It surpassed all his previous enterprises. It advanced certain patterns from the 1937 Golden Gate Bridge and the 1939 Bronx-Whitestone Bridge to the next higher level, one even more refined, subtle, and sophisticated.

Moisseiff's bold and innovative vision of the Narrows Bridge kindled the imagination. The Narrows Bridge would be more than a bridge, more than a crossing. His design lifted the bridge majestically to a great artery, reaching between two evergreen-clad shores. It was not merely a road for cars and trucks, but an artistic and engineering statement. It was the culmination of his outstanding career.

1940 Narrows Bridge, view from centerline WSDOT

Detail view of 1940 tower and cross-bracing WSDOT

Several features of the 1940 Narrows Bridge place it squarely in the modernist, Art Deco traditions. Of course, all of these bridge components had an important practical function. Here, we're focusing on the aesthetics of the design, not the engineering. Let's look at four parts of the 1940 Narrows Bridge in terms of its "art," the towers, the solid plate girder, the anchorages, and the East Entrance.

Towers

Strong, clean lines of the slim towers characterized Moisseiff's design. The 1940 bridge's towers dramatically reflect Moisseiff's aesthetic sense. And, they follow the "modernist" preference for simple geometry and uncluttered lines.

In the slender towers and gentle curve of the cable, the eye sees no glitz, no decorative obstructions. The visual journey is upward, enhancing the drama and splendor of the Narrows environment. The steel shafts soar skyward. The long lines and slim vertical ribs extend and multiply the light.

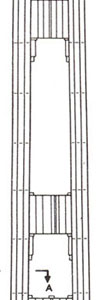

The towers are "battered," that is, they form of an upwardly receding slope, tapering from their 50-foot base to 39 feet at the top. This design element also emphasized the towers' upward thrust and exaggerated the appearance of height. The tower legs outwardly offer sets of clean, vertical lines from the base to the very top of the leg.

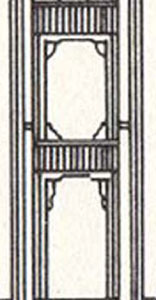

1940 tower face sketch WSA, WSDOT records

1940 pamphlet sketch WSA, WSDOT records

The vertical rib-effect on the tower legs and horizontal bracing struts. This feature echoed the Golden Gate Bridge, as well as major skyscrapers like the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, and the Waldorf-Astoria. It also emphasized height and vertical thrust, as if the towers were a "frozen fountain." This feature also artistically reflects the tall evergreens on the bluffs of the Narrows. The vertical ribs on the horizontal struts echo the rays of the rising and setting sun. They enhance the slenderness of the towers, lifting the eye and spirit.

1937 Golden Gate Bridge tower detail WSDOT

1940 tower sketch detail WSDOT

The stepped-back treatment at the corners of the portals. These treatments echoed the Golden Gate Bridge's own Art Deco embellishments, with their stepped-off giant rectangular portals. One can also view the shape of the portal opening as virtually the same as a skyscraper—a terraced, stepped back pyramid.

The 8-foot deep plate girder of the 1940 Bridge WSDOT

Solid plate girder

Vertical ribs on the solid plate girder echo the vertical motif and movement. These connecting points between the steel plates stretch the full length of the 5,000-foot long girder at 8 ½ -foot intervals.

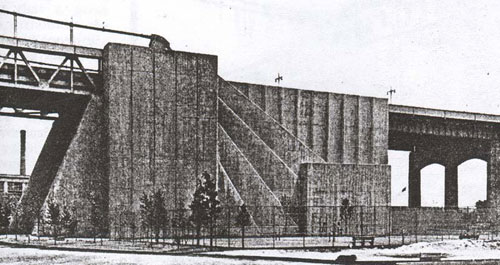

1940 Narrows Bridge, east anchorage view GHM, Bashford 2763

Anchorages

Anchorages often are overlooked, but artistically they are as important as the towers. The anchorages of the 1940 Narrows Bridge reflect the economy and simplicity seen prominently in the towers.

In the geometric lines of the anchorage we see a design that is functional and refined, without embellishment or decoration. The massive concrete form is shaped with specific imagery in mind. Here, the architectural treatment visually brings the cables to an ending point where they disappear from sight.

The bold lines convey the tremendous tension of the cables with power and economy. At the same time, the shape suggests a dynamic counterbalance to the cable's great pull.

The geometric motif on the anchorages resembles two other spans Moisseiff helped design, the Triborough Bridge and the George Washington Bridge, both Othmar Amman bridges in New York. The influence of Art Deco geometry is clear when we compare the Narrows Bridge's anchorage with the 1931 George Washington Bridge and the 1936 Triborough Bridge.

1940 Bridge east anchorage, sketch 1939 WSA, WSDOT records

Anchorage, George Washington Bridge, 1931 WSA, WSDOT records

Anchorage, Triborough Bridge, 1936 WSA, WSDOT records

East entrance

1940 East Entrance showing toll plaza, lamp post and sign GHM, Bashford 2780

Toll plaza, light posts, and signage

Here, too, clearly stamped are modernist and Art Deco influences. The light posts feature curved bands at their bases. Rounded lettering of the signs at the eastern entrance to the toll plaza reflect styles of the period. On the left side of the entrance, the concrete curved with the words, "Gateway to Olympics," and on the right side, "Tacoma Narrows Bridge." The curve shapes create a sense of flow and movement toward the dramatic towers.