Tacoma Narrows Bridge history - Community connections - Collapse

"Galloping Gertie" collapses November 7, 1940

One fateful day changed the course of many lives and bridge engineering history.

What's here?

- Correcting the "Bounce" - Too late

- No one expected the collapse

- The fateful day unfolds

- "Last Man on the Bridge" and other adventures

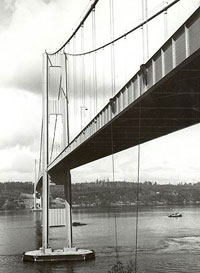

Collapse of the 1940 Bridge. GHPHSM, Bashford 2786

Correcting the "Bounce" – Too late

To engineers Gertie's "bounce" represented "structural instability." They set about trying to fix the "vertical oscillation."

From the first week of May 1940, as workmen finished the bridge's floor system, engineers and others noticed the deck's vertical wave motions, or "bounce." They knew something was wrong. Months before, in the summer of 1939, they had heard rumors of similar small waves in another suspension span, the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge, which opened in April 1939. The Bronx-Whitestone Bridge, like the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, had been designed by consultant Leon Moisseiff of New York.

They contacted Moisseiff. He admitted that two of his latest bridges (the Deer Island Bridge and the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge) were experiencing similar movements, though on a much smaller scale.

In May 1940 engineers tried to take the "bounce" out of the bridge. They installed four hydraulic jacks ("buffers") at the towers to act as shock absorbers. But, the devices made no noticeable improvement.

Immediately, the Toll Bridge Authority contracted with engineering Professor F. Bert Farquharson at the University of Washington to conduct wind tunnel studies and recommend a remedy. Farquharson built a 1:200 scale model (54 feet long) of the entire bridge with the help of some of his students. They also made a 1:20 scale model (8 feet long) of a section of the bridge' deck. The studies cost $14,500.

Farquharson later said, "We knew from the night of the day the bridge opened that something was wrong. On that night the bridge began to gallop." He carefully monitored the bridge's movements. He noted wind speed and the size and shape of Galloping Gertie's vertical oscillations.

In October, while the wind tunnel studies continued, engineers placed "temporary" tie-down cables (anchored restraining wires 1-9/16 inches in diameter) on the bridge's side spans some 300 feet out from each anchorage. At mid-span they placed diagonal wires between the main cables and the deck. (Additional tie-down wires from the tower tops to the decks were considered but never tried.)

View of 1940 Narrows Bridge, looking west from the Tacoma side. Note tie-down cables attached to side span in foreground. WSDOT

Farquharson and state bridge engineers believed they had solved the problem. On November 1, the east tie-down cable broke in a high wind when Gertie began to "gallop." Workmen immediately began repairs. The tie-down cables did reduce the "bounce" in the side spans, but they had no effect on the center span.

That autumn several storms lashed the bridge. Winds over 50 miles per hour blasted Gertie. She remained steady, showing no hint of what was to come.

During the studies, Professor Farquharson noted under certain conditions a "twisting motion" on the bridge model. "We watched it," the professor later told reporters, "and we said that if that sort of motion ever occurred on the real bridge, it would be the end of the bridge."

Farquharson could not complete the studies until November 2nd. Other projects relating to federal government defense research had to take priority over Farquharson's study of the Narrows Bridge.

The probable cause of Gertie's instability, Farquharson reported to the State Toll Bridge Authority, were the bridge's solid stiffening girders. He offered a choice of remedies: either allow the wind to pass through by cutting holes in the solid girders; or deflect the wind by covering the girder with sections of curved steel ("fairings").

Shock: No one expected the collapse: Almost no one

The Narrows Bridge had been designed by one of the most eminent and respected bridge engineers in the world. Federal and state and experts had approved the plans. The bridge was a state-of-the-art structure. It had cost over $6 million to build. Besides, no suspension bridge had failed for decades. And, generally in the early 20th century, people placed great faith in the power of modern machines.

The state's engineers told local newspapers that the "bounce" was normal. They were in the process of installing motion damping devices and safety measures. There was no reason for the public to be alarmed at Gertie's gallop.

The State Toll Bridge Authority felt optimistic. They were delighted with the popularity of the bridge and the revenues it generated. They were taking a close look at the bridge's insurance policies, hoping to replace them with new ones that carried a lower premium payment. They knew the bridge had trouble with its "bounce" and had contracted with Professor Farquharson to devise remedies.

But, some bridge workers thought otherwise. As the bridge neared completion in May 1940, "the ripple" alarmed several workmen. They chewed on lemons to counteract seasickness from the motion. Some believed that Galloping Gertie would go down in a matter of months.

"I'll bet you the bridge won't last a year," said F. S. Heffernan to Ted Coos. Heffernan's company (Glacier Sand and Gravel) supplied sand and gravel for the entire project. Coos worked as a design engineer for Pacific Bridge Company. When the bridge actually failed, Heffernan was as upset as everyone else. "I couldn't take the money now," he said sadly.

On November 7th, just five days after Farquharson finished the studies, State authorities were drafting a contract to install the wind deflectors. Bridge engineer Clark Eldridge had met with Professor Farquharson and PWA engineer L. R. Durkee the day before. They agreed on a course for "streamlining" the south side of the center span. On November 7 Eldridge began preparing the sketches and getting prices for steel and other materials. In 10 days the bridge would have enough wind deflectors to achieve significant stability, if wind came from the south. In two weeks the south side of the center span would be fully covered with the protective deflectors. In 45 days the entire bridge on both sides would be covered. Eldridge and Farquharson felt optimistic.

That morning icy winds gusted up the Narrows into the side of Gertie's deck. Time ran out.

The fateful day unfolds

In the early morning hours of November 7, 1940 strong winds blew through the Narrows from the southwest. They blasted Gertie broadside, directly against the deck's solid plate girder. The bridge began undulating, "galloping," with several waves 2 to 5 feet high. At 7:30 a.m. the wind measured 38 miles per hour. Two hours later, engineers clocked the wind at 42 miles per hour near the bridge's east end. But, near the west end, fishermen reported the wind speed was "substantially" higher than that.

Around 8:30 a.m. engineer Clark Eldridge drove across the bridge. The center span was doing its familiar wave, less than other days. He returned to his office a mile away.

About 9:30 a.m. Professor F. B. Farquharson arrived at the bridge, after an hour drive from Seattle. He began taking motion picture footage and still photos of Gertie's "ripple" for his engineering studies.

Between 9:30 and 9:50 a.m. the last cars to safely cross Galloping Gertie paid their tolls and drove west toward Gig Harbor.

Hear Winfield Brown's account (mp3)

Read Story

About this time, a college student from the University of Puget Sound, Winfield Brown, walked onto the moving bridge to get "a thrill for a dime." Brown reached the west tower and returned. Then, he turned and again walked west, hoping to get a look at the Coast Guard vessel Atlanta that soon would pass beneath the bridge.

Gertie begins torsional oscillation shortly after 10 a.m. WSDOT

Just before 10:00 a.m., a delivery van for the Rapid Transfer Company paid its toll at the plaza and drove westward. Next came Leonard Coatsworth, a news editor for the Tacoma News Tribune. Coatsworth was driving to the family's summer cottage on the Peninsula. In the back seat rode his daughter's dog, a black spaniel named "Tubby." Coatsworth paid the toll and drove onto the rippling span.

10:03 a.m. Suddenly, the roadway began a "lateral twisting motion." At first the movement was small. By 10:07 the movement became gigantic. The roadway tilted up to 28 feet on one side then the other at an angle up to 45 degrees. Every 5 seconds the bridge deck rose and fell violently with the twisting wave.

Hear Ruby Jacox's account (mp3)

Read story

On the other end of the bridge, near the West Tower, sat the Rapid Transfer Company van with passengers Ruby Jacox and Walter Hagen. They jumped from the van just seconds before the tilting roadway tipped it over. The two clung to the curb for dear life.

When the galloping-twist began, highway officials and State Police quickly closed the bridge. They allowed only the press and Professor Farquharson onto the rolling span. Two workmen, J. K. Smith and W. H. Kreiger, were at their jobs inside the East Tower. The noise became so loud and disturbing they fled to safety at the toll plaza.

Leonard Coatsworth's car on tilting Gertie

Coatsworth had just passed the East Tower when the road tilted sideways and threw his car against the curb. He climbed through an open window and sprawled onto the road. He began crawling to the East Tower, 150 yards away. Coatsworth tried hollering to Brown. The two haltingly staggered toward the tower.

From the East Tower, Coatsworth got to his feet and stumbled toward to the Tacoma end of the span, some 480 yards distant. He reached the toll plaza, told the attendant about the dog in his car, then telephoned his office.

The Tacoma News Tribune immediately dispatched photographer Howard Clifford and reporter Bert Brintnall. The Tribune contacted freelance photographer James Bashford, who hastily headed for the bridge.

Farquharson remained near the East Tower taking motion picture footage. Walter Miles telephoned Clark Eldridge to tell him to come to the bridge because it was "about to go."

Gertie twisting. GHPHSM, Bashford 2784

10:03 a.m. first section of concrete from roadway splashes into the Narrows below Galloping Gertie. WSDOT

Around 10:15 a.m., Clark Eldridge arrived at the bridge. He saw it "swaying wildly" with the bottom side visible as it tilted. Several people were struggling off the roadway at the east end. He joined Farquharson at the East Tower to discuss the situation. They returned to the east anchorage to warn people to stay off the span.

Around 10:30 a.m., a large chunk of concrete dropped out and fell from a section on the west side of the center span. On the west end workmen backed a truck out onto the rolling bridge to rescue Ruby Jacox and Walter Hagen.

On the east end, Farquharson continued taking photos. Clifford, Bashford, and Brintnall arrived. Clifford began taking photographs and ventured onto the span, joining Farquharson. Now, another cameraman, Barney Elliott from The Camera Shop, stood on the twisting bridge taking motion picture footage.

For a short period, the wind subsided and the span steadied itself. Photographer Howard Clifford ventured onto the center span to save Tubby, but had to turn back. He stopped at the East Tower and resumed taking photos.

Farquharson continued his observations, taking photographs and motion pictures from the vicinity of the East Tower. He still believed that the bridge would settle down.

About 10:55 a.m., some 6 minutes before the bridge began to fail, Farquharson (who loved dogs) decided to try to save Tubby. But, when he reached into the car, the terrified dog bit his finger. The professor stumbled back to the East Tower just in time.

By 11:00 a.m. the extreme twisting waves of the roadway, magnified by the aerodynamic effect of wind on the sides of the bridge, began to rip the span. Huge chunks of concrete broke off "like popcorn" (in the words of one witness) and fell into the chilly waters far below. Massive steel girders twisted like rubber. Bolts sheered and flew into the wind. Six light poles on the east end broke off like matchsticks. Steel suspender cables snapped with a sound like gun shots, flying into the air "like fishing lines," as Farquharson said.

The strange sounds of the bridge's writhing filled the air. When the tie-down cables failed, the side spans began to work the main cables back and forth. The movement shifted the steel covers where the cables entered the anchorage, producing a metallic shrieking wail. By now, several hundred bystanders stood on the eastern shore of the Narrows. From the bluff, a workman on a pile driver repeatedly tooted his whistle to try to warn the approaching Coast Guard cutter, Atlanta, which passed under the bridge. The shrill whistle blasts mixed with the howl of gusting winds and the grinding and screeching of metal and concrete. The wild noises gave onlookers a sense of dread and impending calamity.

At 11:02, a 600-foot long section of roadway in the eastern half of the center span (the "Gig Harbor quarter point") of the heaving bridge broke free. With a thunderous roar, the massive section wrenched from its cables in a cloud of concrete dust, flipped over, and plummeted 195 feet into Puget Sound. A mighty geyser of foam and spray shot upward over 100 feet. Great sparks from shorting electric wires flew into the air.

Farquharson ran from the East Tower toward the Toll Plaza, covering the 1,100 feet of the side span length as fast as his legs could carry him. He followed the centerline, where he knew there was least motion. Twice, the roadway dropped 60 feet, faster than gravity, then bounced upward, finally settling into a 30-foot deep sag. Just in front of him Howard Clifford ran, fell, and scrambled up the roadway.

Last man on the bridge and other adventures

Hear Leonard Coatsworth's account (mp3)

Read Story

Successive deck sections rapidly fell out toward each tower. Coatsworth's car and Tubby followed the plunging roadway into the wind-swept Narrows.

By 11:10 a.m. it was over. The cold waters churned, eddied, and swirled. The heart of Galloping Gertie sank beneath whitecaps, coming to rest on the bottom of Puget Sound.

Huge splash as final section of bridge collapses, 11:10 a.m. on November 7, 1940. The copyright in this image is the property of the Tacoma Public Library. Any additional copies or reproduction of this image are prohibited. All rights reserved

Ruined bridge, view from southeast, November 1940. The copyright in this image is the property of the Tacoma Public Library. Any additional copies or reproduction of this image are prohibited. All rights reserved

Morning after the great collapse, November 8, 1940. The copyright in this image is the property of the Tacoma Public Library. Any additional copies or reproduction of this image are prohibited. All rights reserved

By this time, hundreds of cars bumper-to-bumper were driving to the bridge, making their way west on 6th Avenue from Tacoma and clogging side streets.

The most spectacular failure in bridge engineering history was over. The world's third largest suspension bridge, the latest and most advanced in its sleek design, was a twisted tangle of steel and broken concrete.